In this transcript of a retreat talk, Trevor Miller offers an outline for Understanding Desert Monasticism.

DESERT FATHERS

In the early centuries of the Church’s history, spreading as it did along the trade routes of the Middle East and the Mediterranean and Aegean coastlands, places of worship were the homes of believers or the open air, wherever they could meet unseen because there was much persecution of the followers of Christ.

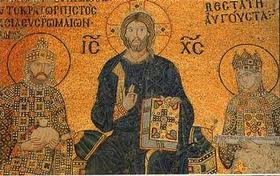

This all changed early in the 4th Century, when the Roman Emperor Constantine embraced Christianity, elevating it to the state religion through the Edict of Milan in 313 AD and by doing so ushered in a major cultural shift. After 3 centuries of ‘being homeless in the world’ Christians began to find themselves in favour, rather than persecuted. The result was confusion and bewilderment in those who had accepted themselves as aliens and strangers in this world. Many accepted Constantine’s edict of toleration but it resulted in the cutting edge of the Church’s life being blunted as for the first time nominalism took root (believers in name only) further resulting in mediocrity, accommodation and compromise as social standing became the reason for faith and not love of Jesus Christ.

This all changed early in the 4th Century, when the Roman Emperor Constantine embraced Christianity, elevating it to the state religion through the Edict of Milan in 313 AD and by doing so ushered in a major cultural shift. After 3 centuries of ‘being homeless in the world’ Christians began to find themselves in favour, rather than persecuted. The result was confusion and bewilderment in those who had accepted themselves as aliens and strangers in this world. Many accepted Constantine’s edict of toleration but it resulted in the cutting edge of the Church’s life being blunted as for the first time nominalism took root (believers in name only) further resulting in mediocrity, accommodation and compromise as social standing became the reason for faith and not love of Jesus Christ.

It was at this point, when Christians began to find themselves at home in the world, where those who had previously persecuted the Christians were putting out the welcome mat and sitting in the ‘same pew’, that the response to the ‘call of the desert’ began to gain momentum, beginning at first with a few, and then a multitude.

Thomas Merton wrote “It should seem to us much stranger than it does, that this paradoxical flight from the world attained its greatest dimensions (I almost said frenzy) when the ‘world’ officially became Christian.”

Was this Christian withdrawal into the desert purely a negative move? Was it a retreat from all the complications and compromise in those attempting to Christianise society? Was it a judgmental act, motivated to shame those Christians who had decided to stay and work out their salvation in the city? Which group of Christians made the right response to this new and ‘favourable’ situation, those who stayed in the ‘city’ or those who withdrew to the desert? In the mystery of God the answer has to be – BOTH.

One of my favourite stories, which I think will illustrate this point, comes from Elizabeth Goudges’ book on the life of St Francis of Assisi. There is a moment when St Francis meets with Cardinal John, and the two embrace. You can imagine the scene, Francis in his robes of poverty and the cardinal dressed elegantly. Yet as they embrace they realise they share the same heart and devotion for the Lord. Yet, one is called to the temptations of poverty, and the other to the temptations of riches or, to put it another way, one is called to the temptations of the desert, and the other to the temptations of the city.

The moral of the story is that we each have to follow our vocation; to be who we are. Our Hild liturgy puts it well as we each pray, ‘Lord, show me the right seat; Find me the fitting task; Give me the willing heart.’

The Desert Fathers and Mothers retreated to the outskirts of the cities and into the Deserts of Egypt, Syria and Palestine to think through the meaning of such change and to find a different way of being a Christian in the world.

Paradoxically so many people came to them for spiritual guidance, help and instruction so that within 50 years eyewitness accounts reported that the population of the desert equalled that of the towns. Some of the pilgrims stayed and this became the beginnings of Community. However, the Desert Fathers again sought solitude and withdrew from the new Community expression but the cycle repeated itself, resulting in many Communities springing up all over. Much of what was taught was in the form of pithy sayings and observations of wisdom. Here is a good example:

Paradoxically so many people came to them for spiritual guidance, help and instruction so that within 50 years eyewitness accounts reported that the population of the desert equalled that of the towns. Some of the pilgrims stayed and this became the beginnings of Community. However, the Desert Fathers again sought solitude and withdrew from the new Community expression but the cycle repeated itself, resulting in many Communities springing up all over. Much of what was taught was in the form of pithy sayings and observations of wisdom. Here is a good example:

A brother came to visit Abba Sylvanus at Mount Sinai. When he saw the brothers working hard, he said to the old man, “Do not work for food that perishes, for Mary has chosen the good part.” Then the old man called his disciple, “Zachary, give this brother a book and put him in an empty cell.” Now when it was three o’clock the brother kept looking out of the door to see if someone would call him for the meal. But nobody called him, so he got up, went to see the old man, and asked: “Abba, didn’t the brothers eat today?” The old man said, “Of course we did.” “Then why didn’t you call me?” he said. The old man replied, “You are a spiritual person, and do not need that kind of food, but since we are earthly, we want to eat and that’s why we work. Indeed you have chosen the good part, reading all day long, and not wanting to eat earthly food.” When the brother heard this he repented and said, “Forgive me, Abba.” Then the old man said to him: “Mary certainly needed Martha, and it is really by Martha’s help that Mary is praised’.

MONASTICISM

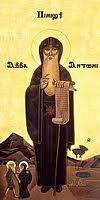

Antony of Egypt is generally regarded as the original desert father. He exemplified the Anchorites, those who were largely hermits, living in isolation. His life became the first written account of the monastic expression becoming widely read and revered.

Community life in a monastic sense first appeared with Pachomius in the 4th Century. These were Cenobites, paradoxically described by Pachomius as ‘a community of hermits’, each living alone in their own cells yet together in work and worship.

The term Monasticism helps us to answer the question, what is a monk? The root word Monachos means ‘alone, solitary’. In the beginning it stood for the ascetic who was not married and lived alone. Cenobites did not use this word in the beginning preferring ‘brother’. However it quickly acquired a deeper meaning: a person who is ‘one’ in his inmost being. It means a person united within himself, a person with a single gaze, a single desire. Monos = monk, one, single minded; and this ‘one thing necessary’ was seeking God in repentance because it was a continual confrontation with the Cross, with self, with sin, with the wrong of the world.

The term Monasticism helps us to answer the question, what is a monk? The root word Monachos means ‘alone, solitary’. In the beginning it stood for the ascetic who was not married and lived alone. Cenobites did not use this word in the beginning preferring ‘brother’. However it quickly acquired a deeper meaning: a person who is ‘one’ in his inmost being. It means a person united within himself, a person with a single gaze, a single desire. Monos = monk, one, single minded; and this ‘one thing necessary’ was seeking God in repentance because it was a continual confrontation with the Cross, with self, with sin, with the wrong of the world.

The link between Celtic spirituality and desert spirituality is monasticism and Celtic spirituality embraced the meaning of the desert symbolically and metaphorically. Jesus used the term ‘desert’ in this way – a good example is Mark 6:31 where Jesus using the word for desert says ‘Come with me by yourselves to a quiet place and get some rest’ Not a reference to desert dryness, uninhabited waste but a picture of solitude, stillness, the heart alone with God. Same word used in Luke 4:42 ‘At daybreak Jesus went to a solitary place.’ Also Luke 6:12, 9:18, 11:1 – a place of privacy, aloneness, often whole nights in close company with his Father, expressive of his single minded devotion to the Father’s will. Latin = solitudo. Russian = Poustinia, Greek = Eremos – stillness, desert, lonely place. A further understanding was seen in the example of the Temptations of Jesus. The desert for Jesus was a period of testing and discovery and just as He was ‘led by the Spirit into the desert to be tempted of the devil’ so it would be for those who sought to follow Him. There is a strong tradition that Jesus (like his cousin John the Baptist before him) spent many of the so called hidden years in the desert regions. Jesus spent 18 years hidden; and only 3 years in public ministry.

So putting these together the desert was not just a place, a physical location but a type of Christian experience. It was a journey – an inner journey of the heart. The Bible begins in a Garden and ends in a City but much of the terrain in between is a desert. This was the ethos of what became monasticism – the inner journey of abandonment, stripping away, a place of encounter and discovery, of identity and vocation, of testing and preparation of heart for the life God has for us.

So putting these together the desert was not just a place, a physical location but a type of Christian experience. It was a journey – an inner journey of the heart. The Bible begins in a Garden and ends in a City but much of the terrain in between is a desert. This was the ethos of what became monasticism – the inner journey of abandonment, stripping away, a place of encounter and discovery, of identity and vocation, of testing and preparation of heart for the life God has for us.

NORTHUMBRIA COMMUNITY

As a Community we are following on in our own generation this tradition. Our core vision is to respond to the call of God to seek Him in and through the embracing, exploring and expressing of a new monastic spirituality as a different way of living in and relating to, today’s world.

This is our heart, our reason to be, the constant theme of Psalm 27. ‘One thing I ask of the Lord, this is what I seek; that I may dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life. To behold the beauty of the Lord and to seek Him in His temple.’ It is the daily renewal of our vows encapsulated in our morning office ‘Who is it that you seek?’

It is the continual commitment to ‘the one thing necessary.’ Single minded focus on the mystery of God in Christ, who is the Way, the Truth and the Life, not only in the narrow ‘evangelical’ interpretation of doctrinal exclusiveness but in the deeper awareness that all things come together in and through Christ. Then to offer the fruit of our life in incarnational ordinariness with all who come our way, cross our path in the everydayness of our roles, responsibilities and relationships, asking with them ‘How then shall we live? How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?’

BACKGROUND

As a Community we have been and are united in this quest for ‘a new monasticism’ a Northumbrian spirituality. Not as an escapist, nostalgic quest for a golden era that didn’t exist or to replicate the past but informed by the Celtic monastic tradition which is our heritage, we are ‘looking with them to Him who inspires us both’ in order to find a way to engage with the paradox and complexities of real life as it is, by drawing from the well of faith and love for the Lord expressed in that period of our history, and applying it to our contemporary situation.

Two of the more significant milestones in the journey of seeking to understand ourselves was a] the discovery of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and in particular his belief that ‘The renewal of the church will come from a new type of monasticism which only has in common with the old an uncompromising allegiance to the Sermon on the Mount. It is high time men and women banded together to do this’

Two of the more significant milestones in the journey of seeking to understand ourselves was a] the discovery of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and in particular his belief that ‘The renewal of the church will come from a new type of monasticism which only has in common with the old an uncompromising allegiance to the Sermon on the Mount. It is high time men and women banded together to do this’

And b] strongly identifying with those believers described by William Stringfellow in his book ‘An ethic for Christians and other aliens in a strange land’ as the hidden future of the Church ‘Dynamic and erratic, spontaneous and radical, audacious and immature, committed if not altogether coherent. Ecumenically open and often experimental, visible here and there, now and then but unsettled institutionally. Almost monastic in nature but most of all enacting a fearful hope for society.’

All this resonated with us as we firmly believed (and still believe) that we are experiencing as a Community, (along with many, many others) a ‘holy restlessness’ and a ‘divine concern’ regarding the nature of faith, which for us has only begun to make sense of the nonsense within us and around us through an embracing of monastic values and disciplines. Why is this? Because these distinct values enable us to ‘marry’ the inner journey, the landscape of the heart – a call to repentance, a call to self denial, and a call to recognise and to resist evil – with the outer journey, the landscape of the land, which has given us a platform to ‘find a different way’ of being a Christian in the society that we live in.

many others) a ‘holy restlessness’ and a ‘divine concern’ regarding the nature of faith, which for us has only begun to make sense of the nonsense within us and around us through an embracing of monastic values and disciplines. Why is this? Because these distinct values enable us to ‘marry’ the inner journey, the landscape of the heart – a call to repentance, a call to self denial, and a call to recognise and to resist evil – with the outer journey, the landscape of the land, which has given us a platform to ‘find a different way’ of being a Christian in the society that we live in.

The whole purpose of the Nether Springs was to have a place, a residential centre, rooted in the spirituality of Northumbria, where we could explore and research this call of God, where we could be ourselves, no pretence or having to behave, while seeking God for Himself and getting to know our own hearts and at the same time, provide a facility for others to join us in their individual search for God.

MONASTICISM OLD AND NEW

In order for us to understand about ‘a new monasticism’ we needed to understand a little about ‘old’ monasticism because it was from that tradition that we drew so much. In this we were influenced by the way of life expressed in the monastic  Community’s at Roslin in Scotland and at Clonfert in Ireland, where Roland Walls and Michael Cullen respectively gave significant example.

Community’s at Roslin in Scotland and at Clonfert in Ireland, where Roland Walls and Michael Cullen respectively gave significant example.

We discovered that monasticism is ‘a way of life with a spiritual goal which transcends the objectives of this earthly life. The attainment of this goal is considered the ‘one thing necessary.’ Christian monasticism i.e. that which is centred in and consecrated to Christ being informed, inspired and illumined by His Love) has three essential elements namely, Separation from the world, Ascetical practices, Mystical Aspiration.

A] Separation from the world – the physical separation of the enclosure; a tonsure, a distinctive habit etc. all of which marked the separateness.

B] Ascetical Practices – Poverty, chastity, obedience, regularity of life in a Community under a Rule, stability, self denial, silence, solitude, cultivation of lectio divina, public prayer of the Church e.g. the story in Exodus 17 where the continuous prayer of the liturgical offices is likened to the holding up the hands of Moses, and engaging in spiritual warfare.

C] Mystical Aspiration – Searching for God in his Absolute Mystery and Beyondness. God is both concealed and revealed. Contemplation of Christ the Living Word and of Christ in the written Word, allowing self to be caught up in the movement of repentance, of returning to God. Giving oneself to His action in us thro Availability and Vulnerability, surrender, abandonment, and prayer.

A new monasticism which is ‘An interior monasticism of the heart’ seeks to draw from these truths and attempts to live a contemporary expression of ‘contemplation in a world of action.’ So the differences are in emphases

A] Separation – not separatism, isolationist but withdrawal as strategic retreat. An awareness of the importance of the inner journey, poustinia, cloister of the heart, solitude, hiddenness, alone yet together.

B] Ascetical practises – a way for living that incorporates the spiritual disciplines to encourage this interior vigilence. Ascesis = training, living. It is training for life needing a Rule of life, a rhythm of prayer, a reason to be. Seeking God, knowing self so as to better live with others. So we have both solitude and Community, both Alone and Together as spiritual disciplines. This is seeking “truth in the inward parts” Ps 51, a life of repentance, humility and teachableness with a willingness to embrace the spiritual disciplines that bring life.

C] Mystical aspiration – awareness of God as Mystery, seeking God, longing, monasticism of the heart, compunction, a contemplative approach to life and prayer where an awareness of the cell, Desert, dark night, inner life, logismoi, monsters is needed. This is where God is concealed from us yet revealed to us in the paradoxical ‘ever-present absence of God’..

All the spiritual disciplines and monastic values are there not as ends in themselves but as aids, tools, signposts to the heart of it all which is Christ. Thus we have many of our daily meditations (e.g. Day 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 17, 21 etc ) pointing to the inner journey as paramount and foundational.

This is our ethos, our heart, that which gives us identity. It is something we can only do alone but we are Together in our Aloneness. We have many Companions sharing our journey. It is the ‘single minded search for God’ given coherence by desert and Celtic spirituality which was essentially monastic and any expression of Monasticism stands in the wisdom tradition which is not an accumulation of knowledge for its own sake, but a constant application to life actually lived ‘A wise person does not gather and dispense insights, but rather has the heart to live those insights’

1] MONASTIC DISCERNMENT – Relationship with God, self and others

2] MONASTIC DISCIPLINE – Rule of life – Availability and Vulnerability

3] MONASTIC DAY – Rhythm of prayer and life, giving a pattern to my days

MONASTIC DISCERNMENT

This was the purpose of going to the Cell. Your cell may have a physical representation; a hut or poustinia, a chair in a corner of a room etc. But whatever it is, it is symbolic of the heart alone with God. This is the heart of the inner journey. It is encounter and discernment of that which is constructive and destructive, enabling us to choose life and not death.

That process of looking inward in order to discover the true self as opposed to the false self, the deeper meaning of all your actions and reactions, and this ‘going to the cell’ would eventually teach you everything and so bring you closer to the true humanity of Christlikeness.

One of the first effects of ‘going to the cell’ is the release of the energies of the unconscious, which gives rise to two different psychological states:-

a] Exposure to the love of God: expressed and experienced in our personal development in the form of spiritual consolation; experiencing his mercy, grace and forgiveness in Christ through his Cross.

b] Exposure to the sinfulness of humanity: experiencing our own human weakness through humiliating self knowledge and encounter with the false self, the dark side of our personality. ‘It takes a moment to get you out of Egypt but a lifetime to get Egypt out of you.’

This dual awareness is what the Fathers called ‘compunction’ and it’s captured in the hymn ‘Beneath the Cross of Jesus two wonders I confess: the wonder of his glorious love and my own worthlessness.

MONASTIC DISCIPLINE

This is why a Rule of life is absolutely essential to any monastic expression. It says this is who we are, this is our story and all  who are part of us must keep to and live in the story that God has written as foundational. Monastic stability is to be accountable to a Rule of life NOT to a set of rules that restrict or deny life. It is, to use the words of Benedict ‘simply a handbook to make the very radical demands of the gospel a practical reality in daily life’.

who are part of us must keep to and live in the story that God has written as foundational. Monastic stability is to be accountable to a Rule of life NOT to a set of rules that restrict or deny life. It is, to use the words of Benedict ‘simply a handbook to make the very radical demands of the gospel a practical reality in daily life’.

A Rule is like a pair of eye glasses (spectacles) – we don’t look AT them but THROUGH them to life. How foolish to constantly look at them, the gold frames the bi-focul lenses and never look through them so as to actually see.

The word comes from the Old English REULE. In Latin it is REGULA which means ‘rhythm, regularity of pattern, a recognisable standard’ for the conduct of life. Esther De Waal writes that the Latin REGULA ‘is a feminine noun which carried gentle connotations’. Not harsh negatives that we often associate with the phrase ‘rules and regulations’ today.

Esther De Waal tells us that the word has a root meaning of ‘a signpost’ which has a purpose of pointing away from itself so as to inform the traveller that they are going in the right direction on their journey. It would be foolish to claim we have arrived at our destination if in fact we are only at a signpost, however near or far from the destination it is.

Another root meaning of REGULA is ‘a banister railing’ which is something that gives support as you move forward, climbing or descending on your journey.

A Rule of life gives creative boundaries and spiritual disciplines while still leaving plenty of room for growth, development and flexibility. It gives us something to hold on to as we journey in our search for God, and when we be blown off course, it gives a safe haven to come back to. It gives us a means of perception, a way of seeing so that we can attempt to handle our lives and relationships wisely. This is why we can all be helped by embracing a

MONASTIC DAY

A workable rhythm to your day that draws from Monastic values that actually works for you according to your own unique situation and circumstances. It has to bring life and freedom not straightjacket you.

Our Rule of life is deliberately flexible and adaptable. It is also timeless because it does not PRESCRIBE, it PROVOKES. It is descriptive rather than prescriptive! It’s the very opposite – its seek God for yourself, who you are, where you are – with your unique experience, knowledge and understanding of life. With all your idiosyncrasies, prejudices and crap – bring it all to the Rule of Availability and Vulneraility. We must hold it loosely so as to make our own discoveries. To realise there won’t always be an answer so we keep asking/living the questions.

How then shall we live? Who is God? Who am I? What is Real?

It is to realise that God gives different answers to different people in different situations and circumstances, which is why we can’t prescribe, can’t meet individual agenda’s and expectations.

In many ways it would be so much easier to say this is the prescription – do this, don’t do that – take 3 Hail Mary’s, 2 Our Father’s 4 times a day. It has to be broad strokes, general principles to which you apply your specifics – your own unique set of circumstances and relationships.

Henri Nouwen expresses it well when he speaks of the spiritual life being a constant reaching out in the midst of paradox and chaos to these three areas of connectedness. This Reaching Out constitute the three Movements of the Spiritual Life.

1] Connecting in relation to self – From loneliness to solitude. With courageous honesty to our inmost selves, facing inner restlessness, our passions, weaknesses.

2] Connecting in relation to others – From hostility to hospitality. With relentless care to others, despite our mixed feelings and hostility.

3] Connecting in relation to God – From illusion to prayer. With increasing prayer to God, facing our doubts, disappointments and darkness. Living in incarnational reality.

It is the call to love God with all our heart, soul, mind, strength – to love our neighbour as ourselves – to love one another as Christ has loved us.